FOOD AND BODY FREEDOM #2: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT WEIGHT PART 1

Introduction:

Weight is an area that I spend a heap of time chatting with clients and students of my group programs about. Unpacking and processing their beliefs, fears and ideas about weight. Over the years that I've been privileged to do this work of supporting folks in their food and body freedom, I've seen weight chat fall under 3 umbrellas if you like.

Weight itself.

Weight and health.

Weight and worth.

Each one intertwined with the other and involving deeply conditioned ideas about their value. In this first post, I'll be addressing the first two, weight and weight intersecting with health. What we need to acknowledge, what we need to address and what we actually know.

Let's dive in.....

Weight

Weight is not a behaviour. It's a metric, just like height. A behaviour would be physical activity patterns or nutrient diversity frequency. This is a key distinction to make and relevant considering how we tend to talk about weight and health. It's also crucial to acknowledge that weight diversity is normal - we are all made differently. At the outset, this is mostly determined by our genetics (estimates sit at around 80%); though much is yet to be discovered about weight.

To better explore this fact, let’s imagine a woman named Becky who has never attempted to manipulate her weight. Who has had free access to food her whole life. Who has been allowed and encouraged to trust her body. As that relates to caring for it - feeding it, supporting it. Who’s been encouraged to accept her body and respect it. This Becky has a natural growth cycle as we all do. Ending around her mid-20’s when her body finds its adult size and shape. This could be considered her first set point. Whereby her body can easefully exist and remain at a weight without conscious control. She is eating to her hunger and fullness. To her preferences and cravings. Moving or not as feels right for her. Doing everything intuitively.

And yet, in this place we ask the question: can her body weight change? Yes. Without intentionally trying to change her weight, the following factors are just a few of what can impact her weight:

- Stress

- Medical conditions

- Medication

- Trauma

- Lifestyle change

- Pregnancy

- Disability

- Financial strain

- Genetics

And can her weight change again from these changes? Yes. For the same reasons again. Both up and down. And this reality of weight change will continue for Becky’s life. Her body will continue to respond to events and the environment to protect her. To provide her what she needs. (Global pandemic anyone?) The change in weight from her mid 20’s to later in life is “normal” and does not have a figure or even estimate in natural variance that we can make. As in we can not say what a “normal deviation” in weight range (set point range) may be. Because it’s not known. And I’d argue we don’t have many people to study with these attributes to their life experience. So we don’t know much. We can make educated assumptions however and I’ll come back to these.

Now, let’s imagine that Becky decides to intentionally lose weight - what do you think will happen?

She's attempting to change her biology - pretty radical when positioned like that right? She's intentionally under-feeding and/or over-exercising to induce a reduction in body weight. The reality of which immediately increases our preoccupation with food (to protect us), lowers how efficient our body is at using the energy it does have (again to protect us) and increases our weight focus. It literally drives internalised weight stigma. It also disconnects us to our body’s needs, where we are less likely to be aware of and attend to our body’s needs as we are now externally focused on a “goal weight.” Ignoring say hunger or fatigue to hit that goal. Resonating with you?

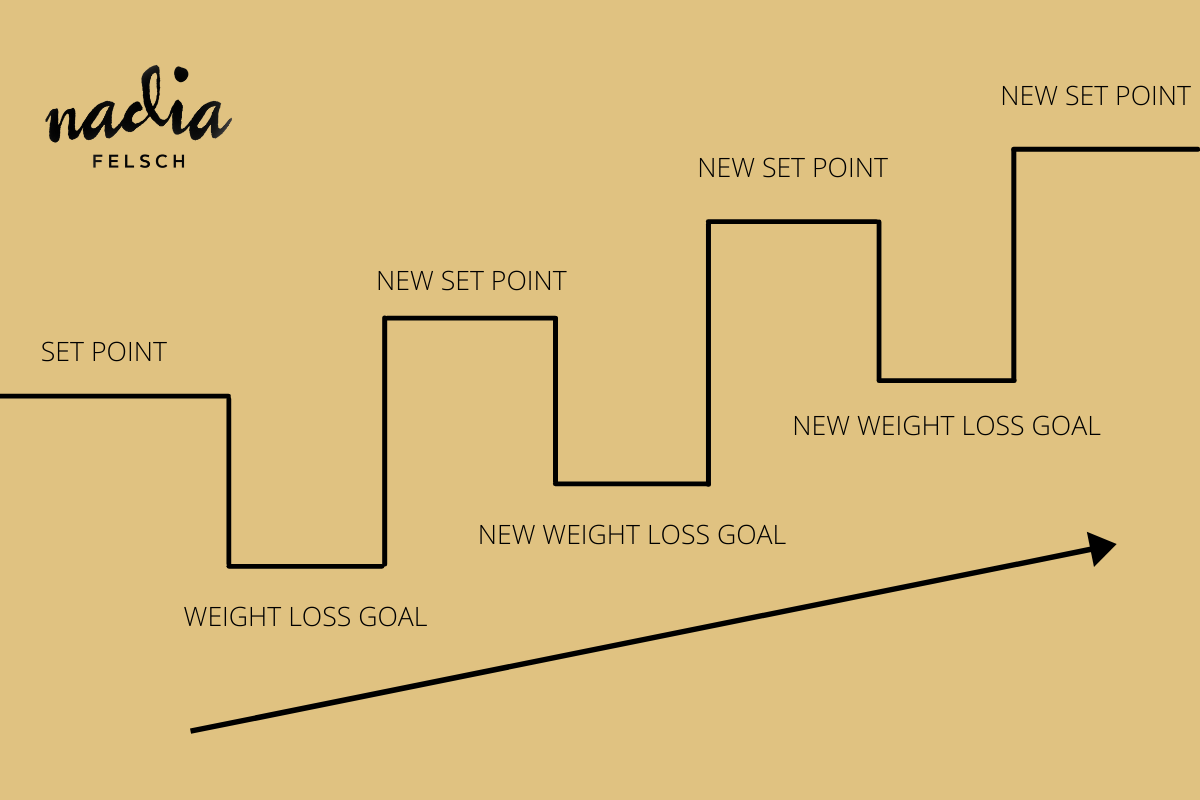

Maybe Becky loses weight. What’s the likelihood of that being sustainable? 5%. And why? It’s fighting biology. And in recovery from intentional weight loss, our set point increases. Our body now works to protect us and provides us the opposite to our aim in weight loss. It makes our new range higher than before. And as you might imagine, maybe it’s your own experience, this continues. And why we say, the greatest predictor of future weight gain, is dieting. Dieting regarded here as any attempt to shrink our body.

So in summary:

- Weight diversity between humans is normal. We see it across other species as Sonya Renee Taylor says so well in her book - The Body is Not an Apology - The Power of Radical Self-Love - including trees, dogs, cows, flowers and yet not ourselves.

- Set point theory is a simple answer to a nuanced answer about what happens to our body size. In short, it's saying that we have a range of “happy” that our body weight will easefully stay at whilst we are honouring its needs. That range can change for a variety of reasons, namely when we try to lower it.

- Our weight is not under our individual control - it’s influenced by 100+ factors.

- Regardless of how, bodies do change. It’s ok.

- Intentionally losing weight is vastly unsuccessful - 95% of the time. It has serious repercussions on health and wellbeing and isn’t much fun. You only need to think to your own experience to know this.

Weight and Health

The accepted assumption is that increased body size = increased health risk. Put another way, if I increase in body weight, I have more chance of developing diabetes and dying. Therefore common wisdom goes, “we need to lose weight / fixate on weight / micromanage weight” to prevent this from occurring.

Upfront, it’s vital to acknowledge that fatphobia; a fear and hatred of fat bodies and anti-fat bias - whereby fat bodies are not preferred and therefore the subject of weight stigma; are deeply entrenched in healthcare. Stigmatising content warning** A 2014 study in the International Journal of Eating Disorders, found that among eating disorder professionals, 35% of practitioners stated they felt uncomfortable caring for those who are ob*se. What does that say? What does that lead to? What type of care would you imagine is offered in these cases? Hearing stories from fat people, I know how common this stigma and bias is. It’s the norm. Consider visiting a healthcare provider as a person in a fat body. Do the chairs fit my body? Does the blood pressure cuff fit me? Will my weight be discussed and used against me? Are assumptions made about my dietary and movement patterns? And even if you're not in a large body, the weight-centric approach that is healthcare means weight and a weight-related focus is the norm, to the absence of more valuable care focusing on actual behaviours. Remember how weight is like eye colour or height, not a behaviour.

So with all this said, here’s what we know about weight and health. Certainly not as much as news headlines would have you think. Weight and health do not have a cause and effect relationship. Meaning one does not directly cause the other. There is causation and association whereby we see particular health risk association with particular weights. And this goes for weights across the BMI spectrum.

A quick note on BMI. It’s a flawed and problematic tool, misused within healthcare. I will be recording an entire episode on BMI in the future, though for this episode, I use BMI to honour the integrity of research on weight and also to more easily group humans together, a much more applicable use of BMI.

In the most relevant study on health risk and BMI relationship (a meta-analysis in 2013), the greatest risk lies in the BMI category known as underweight - those with a BMI below 18.5 and the lowest health risk was in those categorised as overweight with a BMI of between 25 and 30. And yet, this is not the message we receive as individuals or at large.

A large 2012 study reviewing the impact of healthy lifestyle behaviours on mortality across the BMI spectrum of over 11,000 American men and women found that regardless of body size, the more healthy behaviours an individual adopted (including stopping smoking, reducing their alcohol intake, moving their body more and eating more vegetables), the less risk of mortality they had. And it’s this information that’s fundamental to the Health at Every Size approach to health. I’ve talked a fair bit about weight not being a behaviour and in this study, we can clearly see that on display.

Considering the entrenched fatphobia, even in society at large, let’s review the impact of weight stigma and anti-fat bias on health outcomes for a moment. Where we as health providers prescribe weight loss and pressure clients in large bodies to do so and where it has the opposite impact. A 2011 study found that weight stigma is associated with increased caloric consumption, a pattern which challenges the common wisdom that pressure to lose weight will motivate overw*ight individuals to lose weight. A 2009 study found that priming overw*ight women to think about weight-related stereotypes (i.e., inducing weight stigma) led them to report significantly diminished exercise and dietary health intentions

I see this everyday with clients. Where we find ourselves in the cycle of thinking (or being told) we need to lose weight so we try and either it works for a time and then doesn’t, or it doesn’t at all and then what are we left with? From my clinical perspective, we’re left with demotivated, unhappy and less well individuals. So how is this about promoting health? It’s not is the answer. Imagine someone is told they're pre-diabetic (another problematic term but that’s for another time), the common recommendation is to lose weight and yet this is likely to lead to restriction, dieting and weight cycling which is metabolically damaging and adversely impacts our insulin regulation. Instead, we could focus on actual evidence-based healthcare. In this example that might include a focus on consistent and regular eating and establishing a meaningful pattern of physical activity to ensure better managed blood glucose levels in the body. Powerful. Effective. All without a focus on weight.

Our collective thought in society is that focusing on weight brings improved health outcomes and yet weight is not a behaviour so this is flawed from the outset. It’s also clear that weight loss does not automatically equate to improved health outcomes. So if there are health concerns, a decrease in body size doesn’t necessarily mean those concerns reduce/diminish. We also don't know how to make weight loss sustainable or limited in harm for most. And the harm is significant - where weight loss efforts result in weight cycling (this is the set point increase) and can result in disordered eating, negative body image, lowered immune function, decreased bone density and an increased cardio-metabolic risk from weight cycling.

Often we associate feeling better and with weight and that’s not the only thing going on here (I will revisit this in the next part of this series) though for now it’s important to acknowledge that this belief is a consequence of fatphobia and living with our own anti-fat bias. We have created the narrative that being fat is the worst thing that could happen. We shame and stigmatise those who are, in the hope of making them un-fat. And yet what we are collectively doing is making the chance of future weight gain and lower health outcomes more likely.

So in summary:

- Weight loss is not a guarantee of health nor is having a smaller body

- Intentional weight loss is not sustainable for the majority of us

- Intentional weight loss is not without harm

- Even if weight loss was effective at improving health (which again, it isn’t), that’s still no reason to treat humans in fat bodies with disrespect based on their body size. There’s no room for anti-fat bias in ethical healthcare. It’s not ok and it’s killing people.

- Shaming folks about their weight is a poor motivator and we have far better tools to work with when it comes to health behaviours

- Health can be improved without a weight loss target, in fact, it’s likely to be more successful and sustainable

What can we do?

Unpack and unlearn our own weight bias - if you live in a marginalised body, this is likely to be higher. Contribute to dismantling the systems of oppression that exist to make this possible by opting out and calling it out around you. Focusing on what you can do to feel x outcome. Possibly with professional, weight-neutral support. You do not have to lose weight to gain health. And seeing results through actual evidence-based healthcare is possible. For instance a client shared with me recently that in focusing on the behaviour of healing her relationship to food, her dietary pattern is overall more nutrient-dense. Independent of a focus on weight. What might a health goal without weight look like to you?

Part Two coming soon.